The U.S. dollar’s depreciation this year sparked questions about its haven status and a pullback from U.S. assets. We haven’t seen evidence of that so far. We think the dollar has moved in step with historical drivers – not broken with them. The two main drivers of the dollar’s slide are Federal Reserve rate cuts, consistent with surging U.S. stocks, and the return of term premium as global debt concerns come to the fore.

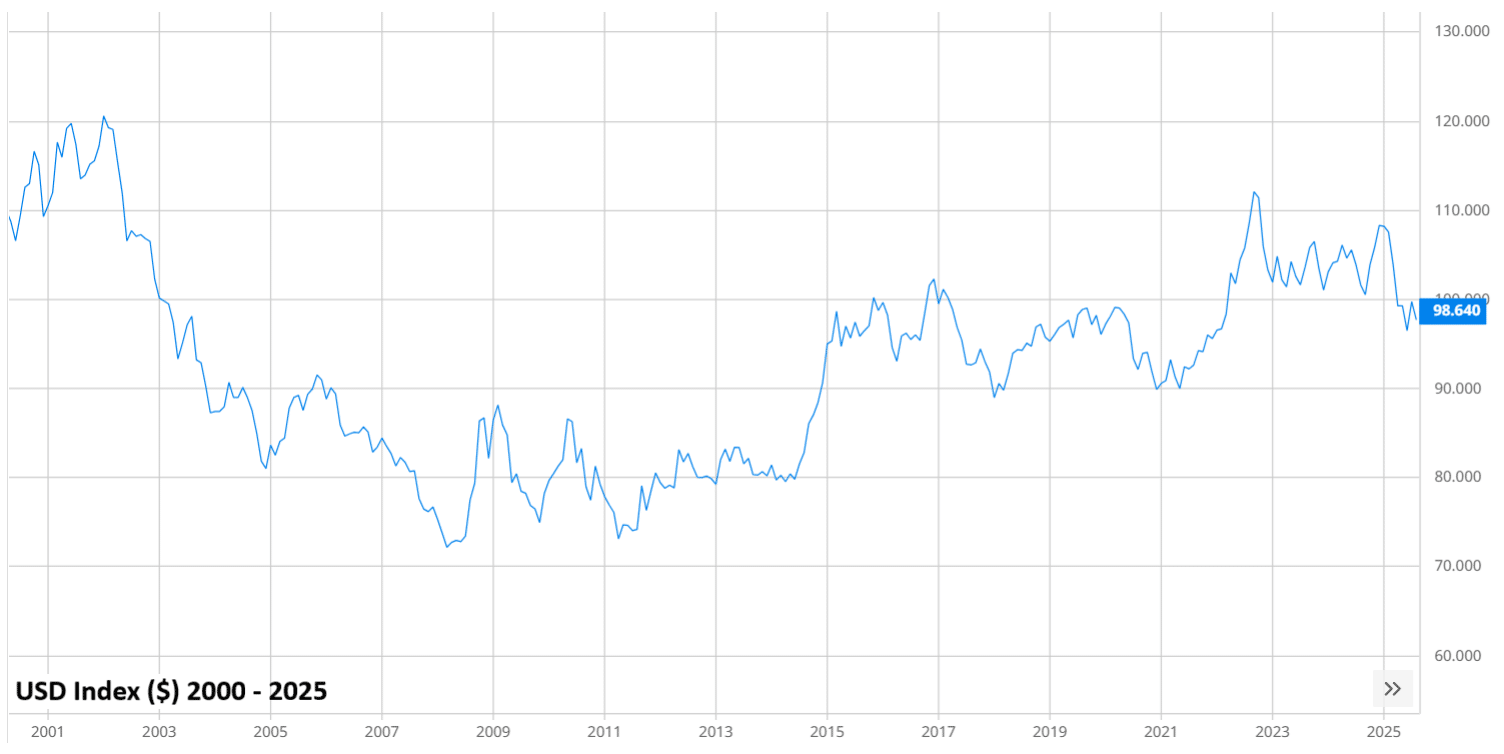

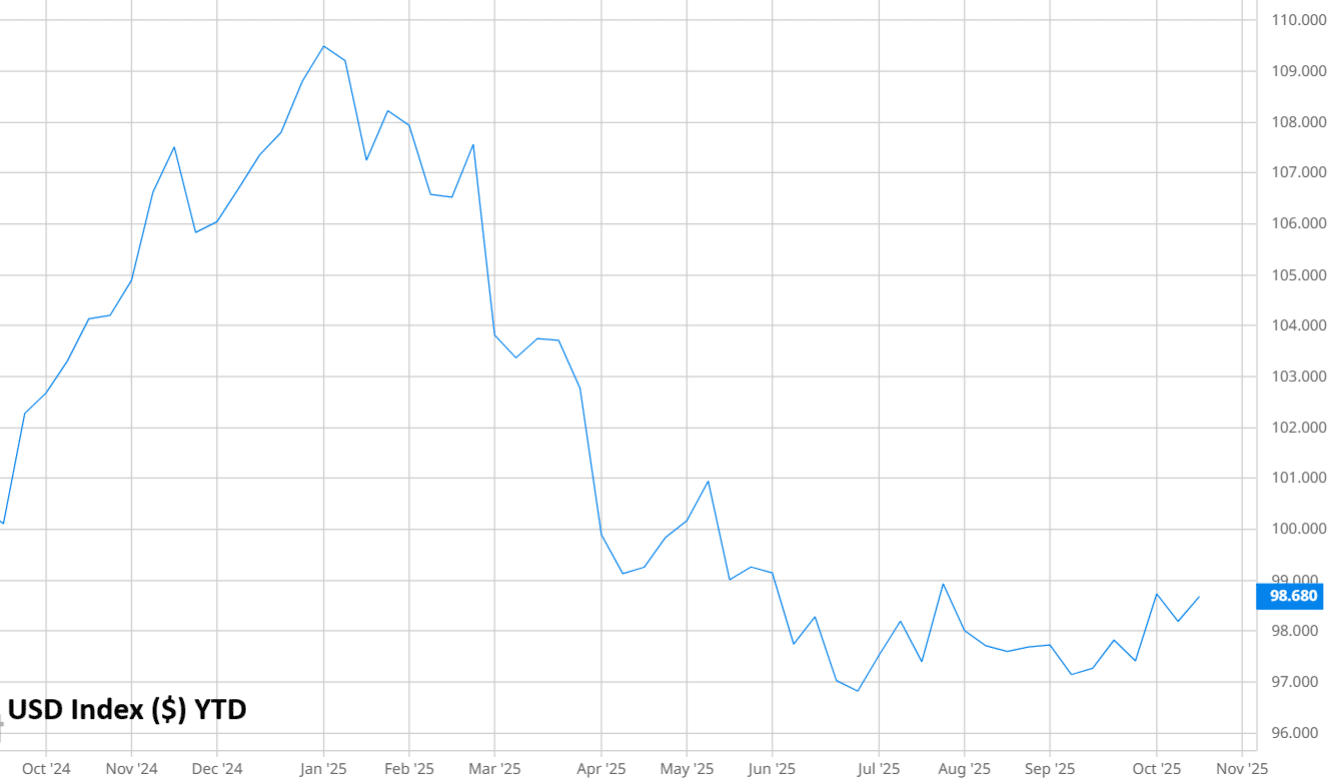

The U.S. dollar has weakened this year – mostly in the first half, including after the April 2 tariff announcements that also hit U.S. stocks and Treasuries. See the right chart. That unusual three-way drop raised questions about the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status and if U.S. assets could lose their appeal – a debate stoked by the summer focus on Fed independence. But the evidence doesn’t yet seem to support such concerns. Yes, the dollar has weakened, but it still looks historically strong versus other major currencies. And it has been mostly flat since the summer, even as tensions around Fed independence grew – holding steady against the euro and strengthening against the Japanese yen. If a structural shift were underway, the dollar would have broken out of its historical relationships with its usual drivers and also weakened against other developed market currencies.

That is not what has happened. Instead, a lot of the analysis carried out by institutions find that the dollar’s decline this year very much tracks with two historical drivers of its value. First, rate cut expectations. Expected Fed easing accounts for about half of the dollar’s drop. Lower rates erode the dollar’s yield advantage over other major currencies. But on the flipside, Fed cuts support U.S. stock gains, already powered by the AI theme.

Global debt concerns return to the fore

Second, the steepening of the yield curve as global debt concerns come to the fore. For years, investors flocked to long-term bonds based on their perceived stability, depressing term premium or compensation for the risk of holding these bonds. Below historic norms even as government debt mounted. Institutions like BlackRock have long highlighted this as a fragile equilibrium that could not hold indefinitely. Indeed, term premium is now returning to more normal levels as concerns about the cost of servicing that debt mount. These fiscal challenges aren’t unique to the U.S.; they are pushing up bond yields and weighing on developed market currencies across the board. That’s why the U.S. dollar hasn’t weakened relative to these currencies – but why all of them have weakened relative to gold.

BlackRock think that lower rates and the AI theme will still support U.S. stocks but eye selective opportunities elsewhere. In Europe, they have favored Spanish equities, up nearly 60% this year in U.S. dollar terms, MSCI data show. BlackRock went on to say that “In emerging markets, we prefer local currency debt, such as 10-year Brazilian government bonds that offer a yield of nearly 14%, according to Bloomberg data. A softer greenback means U.S. dollar-based investors get an added boost when converting back – take the Brazilian real, up nearly 12% this year.” They also see selective opportunities in emerging market stocks: MSCI data show that South Korean and South African equities are up more than 55% this year in U.S. dollar terms. And as rising yields mean long-term developed market government bonds offer less reliable ballast against equity selloffs, BlackRock will look to gold and bitcoin as potential diversifiers of risk and return.

Market backdrop

U.S. stocks slid last week after President Donald Trump on Friday threatened fresh tariffs on Beijing over its latest restrictions on rare earth exports and said a planned meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping was now uncertain. U.S. 10-year Treasury yields dipped but remained in their recent range between 4.00-4.20%. Gold surged past $4,000 per ounce to a new all-time high. The U.S. dollar index hit a two-month high against major currencies before retreating on the tariff news.

The ongoing U.S. government shutdown will likely delay the September CPI and PPI reports. The absence of the key data will keep markets focused on private sector or alternative sets of data until there is a resolution of the shutdown, which could then see this backlog of government data released over subsequent days. The Bureau of Labor Statistics said late last week it would release the latest U.S. CPI on Oct. 24.